Note: As the title of this post implies I wrote this for my not so computer-savvy godsisters and godbrothers, devotee friends, and whoever else might be interested. By no means do I want to insult anyone’s intelligence.

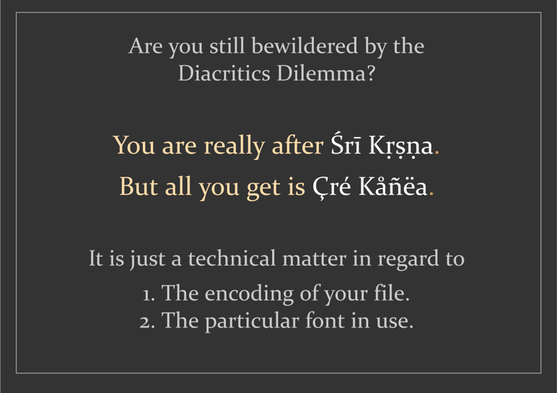

However, after communicating with devotees on the subject I realised that a little guidance would be in order. Many devotees still seem to be struggling with a whole existing load of inconsistently encoded documents – legacy Vedabase encoding – side-by-side with the current, universal, and future-proof Unicode-compliant files.

We are all overwhelmed by technology. To the point that sometimes we may feel stupid in front of the machine. There is no need to feel that way. It is the computer that is stupid. What does “He”

know about typefaces such as “Times New Roman,” “Goudy Old Style,” or “DevaDeva” for that matter? Computers only know two states, ON and OFF, which are represented by the digits 1 and 0. And

combinations thereof. Quite appropriately called ‘machine language’. For everything, really everything, computers require interpretation. Fonts are no exception.

The good news is that it is rather uncomplicated for the user. There is no bad news. Only that a little endeavour is required on your part if you want to enter characters with diacritical marks

yourself (rather than just copying and pasting).

Here are the basics then:

All you have to understand and picture in your mind is how glyphs or characters are mapped to your keyboard. Quite easy. Imagine one of these flat plastic cases with many compartments in a grid

layout. Very much like those storage cases for keeping different screws, nut, and bolts sorted and in easy reach for doing some practical repair work.

Now, referring to fonts, each of theses compartments has a unique label (or address). When you press the lower case ‘A’ on the keyboard you get the lower case A on screen. The computer has no

idea what the lower case ‘A’ is. Being a submissive servant of the servant, the Computer just follows the instruction given to “him”, goes to that unique address and fetches that lower case ‘A’.

( From the particular font family that you have active in your open document )

Simple and easy: it is called keyboard mapping.

But what about all those thousands and thousands of characters (and glyphs) found in the languages of the world? What about the fonts with diacritc marks that we use?

Our keyboards only have a little over a 100 physical keys, after all.

Well, for many years each language of the world (more or less) relied on their own specific keyboard mapping for the then rather limited number of “compartments” (remember the flat case with grid

layout that I mentioned earlier?). The limit used to be 256 compartments, later extended to 512.

The main dilemma was that the world ended up with so many different what is called “encodings”, specific to individual languages and again, key mapping. To work conveniently you needed to have

specific fonts installed on your system. The old isolated island dilemma.

Simply put, document exchange and conversion was a highly painful task. What to speak of the Internet.

The legacy fonts supplied with the Vedabase (at least up to Version 2003.1) fall into this category – and are a case in point.

Now, I want to make one thing very clear: Pratyatosh Prabhu and his son (I believe) did a tremendous service back in the day by modifying a whole range of font families so that we can have those

diacritics. Not only that – he went along with the unfolding new technologies and, to my knowledge has embraced current technology fully. He even provides an on-line converter for legacy encoded

text files. It works like a charm. And it is fast, even for large files.

(On a side note: I only know the Bhaktivedanta Base up to version 2003.1. Later versions may be encoded to current standards—I know that the online version is.)

What then is the current and future-proof technology?

It is an international standard called Unicode. It does away with individual languages cooking their own soup. In brief: all characters of all languages of the world still have their own unique

label and address – as it was before. But instead of a mere 256 or 512 glyphs, a unicode-compliant font can have many, many more.

Thousands.

If a font complies to the Unicode standard, any glyph, be it a Devanagari character, a Lithuanian character – or our transliteration lower case A (ā) with the stroke on top (macron) – has his

unique unchangeable compartment and address. On ALL computer systems and in ALL languages. It will not change or be re-mapped.

Just like you are reading this in your browser right now – if you see this: “Śrī Kṛṣṇa” – correctly with diacritcs, your browser and system are unicode-compliant and configured to be

unicode-aware.

Unicode is not that new, by the way. MS Windows and Macintosh adopted Unicode around the turn of the century. Linux systems are unicode-aware through-and-through, the developers wholeheartedly

embraced it early on.

On your side of things no action is required for using Unicode. All modern operating system are Unicode-aware and come with at least 6 or 7 popular fonts that are not only Unicode-compliant but

suitable for roman transliteration of Indic scripts. Such as in our Vaiṣṇava literature.

In conclusion, if all you need is to read, copy-and-paste for research, and posting on the internet, you are good to go. Just make sure that your application supports unicode (utf-8 encoding) –

most modern applications do. And that you are using a font that has the diacritcs we use – for this you may have to play around a little bit. The main font suspects of your computer system are a

good starting point: Times New Roman or Calibri for instance on Windows. MAC users have at least 10-12 such fonts in their operating system.

If you sure that you are using a font that contains our diacritics and that your file is Unicode (utf-8) encoded and you are still getting words like “Çré Kåñëa” instead of “Śrī Kṛṣṇa” you can conveniently convert your text online:

The old BBT-converter seems to be defunct now.

Please use the highly sophisticated converter made by Pratyatosha Das:

http://pratyatosa.com/?P=41

(It is advisable to keep the files to be converted below 2-3 MB – otherwise the converter may temporarily freeze or crash altogether.

If, however, you – conveniently – want to enter diacritics yourself in your favourite word processor, your plain text editor, or even into a live comment you are making on the internet, some

preparation is required.

But that will be the subject of a follow-up post (Part II) from me – which I will write depending on feedback and interest.